I’ve driven the AA Highway at least fifty, maybe a hundred times traveling to and from my parents’ home in West Virginia over the last fourteen years. The three-hour drive is a perfect time for audiobooks and deep thinking, two things I enjoy but that feel more like consolation prizes for committing to extended time in the car. I can’t say I’ve ever felt excited about the drive, but I always notice something new and interesting once I’m on the road.

Running along the northeastern border of Kentucky, the AA winds long through rolling hills and spacious homesteads, traversing a landscape that cycles through ebullient pastels, verdant greens, and fiery reds, golds, and coppers depending on the season. Each year, the steely grays and smoky browns of winter signal the opportunity for a clean slate, as they make way for a new canvas of color at the first hint of spring.

When the sun goes down, the color goes with it, as the rural expanse fades to black, lit sporadically by oncoming headlights that seem to come from nowhere. That’s when you’d be wise to be on heightened alert, watching for unsuspecting wild animals that are known to venture dangerously onto the highway. Normally, the poor deer, raccoons, or possums would be top of mind given my tendency to drive over the speed limit. But this time I hadn’t given them a second thought. My mind was still in WV.

After a late weekend trip to check on my parents, I was on my way home after a long Monday, tired in a way that makes you feel numb from head to toe. With a bandwidth of basically zero, I tried to focus on making it home quickly, accompanied only by an audiobook to keep me occupied. Last October I had spiritedly chosen to listen to Bram Stoker’s Dracula, a fifteen-hour reading that remained unfinished. A desolate winter drive through Kentucky seemed like an appropriate time to complete it. But as I drove on listening to the deep tones of Tim Curry voicing Dr. Van Helsing, I felt a deep fatigue settle over me. With it came loneliness, a specter in its own right that comes for me when I am most vulnerable. I wished I wasn’t alone.

The highway stretched in front of me like an endless black ribbon flanked by an even darker blanket. My mind began to wander. Although my body felt heavy, I couldn’t have fallen asleep if I tried. Every inch of me was flooded with lingering adrenaline from nearly six months of caregiving and almost constant family stress. I had become an active member of the sandwich generation, although to me life felt more like a lasagna, with too many messy layers stuffed full with sticky, complicated emotions.

My passengers became every life-changing thing that had happened over the last five years. I was of a mindset to accept them all though: the separation, reunification, and separation again from one daughter or the other; finding out I was wrong about who I thought was the love of my life; my mother’s recent health scares; my brother’s battle with addiction; and supporting a college student on a single income. A carousel of fast-moving observations about these events circled my thoughts, returning to the same point at each go-round: my complete exhaustion. Spent in every way, I was too tired to feel.

But I could see.

I had been driving almost two hours when I noticed the fading orange horizon. I felt a rush of gratitude for the distraction. Lost somewhere between Stoker’s tense, seductive words filling my ears and an endless stream of responsibilities filling my head, I realized I had missed most of the sunset.

The last few minutes of daylight reduced the sun to a narrow sliver of orange and gold. Sinking steadily as the night sky descended in its place, the light seemed to wink and flicker a sparkling goodnight. The once colorful trees had turned jet black, outlined sharply against the citrus-hued band. They no longer seemed real, looking instead like a line drawing that my daughter might have carefully sketched in art class.

With the boundary between day and night so stark in front of me, I stopped to honor the passage of time, noting how quickly life can change. We are both mighty and small in our ability to create our own story, which is subject to change in an instant and sometimes comes without our consent. My daughters and I were living a vastly different story than the one we started with. My parents were about to embark on a different story as well. My heart filled with a dizzying mix of sadness and hope at the thought of how our family had changed. It was time for the passing of the torch, from one who is cared for to caregiver. Somewhere along the line I had crossed through a one-way portal to a world I didn’t recognize, but that felt so obvious. My story had changed too for probably the 100th time. I lost count long ago.

I passed a farmhouse that was lit by candles in every window, standing two and a half stories. The shadowy structure, looming tall against the sleepy sunset, seemed welcoming and safe. I imagined the people inside were waiting for someone to come home, a feeling to which I could deeply relate. This was someone’s safe place. I kept driving, determined to reach mine, and also knowing that if I never made it back home I would always be the safest place I’ve ever been. I found stillness and comfort in that thought.

The black of night settled in place around me and I turned my attention back to the book, which I realized I had stopped listening to a few miles back. I had missed Dr. Van Helsing’s plot to destroy Count Dracula with the power of the light in a race against the setting sun.

I continued home feeling lucky to have glimpsed the last flash of sunlight before the horizon closed her eyes for the night. Having laid my demons to rest, I knew I would soon do the same and begin again tomorrow.

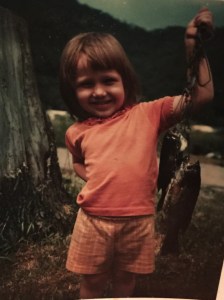

“Daddy! Daddy! Daddy!” I shouted over and over, trying desperately to hold the line as the creature on the other end resisted and fought. Satisfied that he had provided me with an authentic “catch” experience he stepped over to help, and the two of us reeled in a fish that was about half my size (which means it was pretty small). He smiled at me and said, “Well look there baby. I’ll make you a fisherman one of these days.”

“Daddy! Daddy! Daddy!” I shouted over and over, trying desperately to hold the line as the creature on the other end resisted and fought. Satisfied that he had provided me with an authentic “catch” experience he stepped over to help, and the two of us reeled in a fish that was about half my size (which means it was pretty small). He smiled at me and said, “Well look there baby. I’ll make you a fisherman one of these days.”